Only July 8, the Eighth Judicial District in Nevada issued an order allowing a high-profile…

Jury Box v. Ballot Box: The Age of Trump Poses Significant Risk to Corporate Defendants in the Courtroom

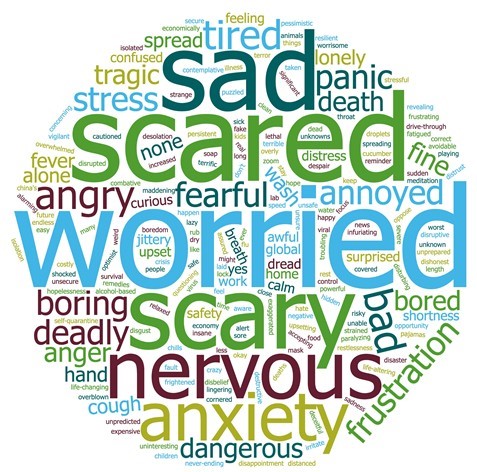

How is Trump going to affect my jury? No question has been asked more by our clients in the last few months. The Executive Orders and the accompanying protests, the nominations and the associated outcry from political opponents, and the composition of the cabinet and other appointments suggests that political activism and anti-corporate sentiment will become far more pervasive and intense in the years to come. Will this activism, however, manifest itself in the jury room? Will corporate defendants find themselves facing more hostile juries, and should they be worried about jurors using jury duty as an opportunity for social activism? It’s still early for definitive conclusions but the prognosis thus far is troubling.

Anti-Corporate Sentiment Unites Factions on the Left and the Right

“Polarization” has been a hot topic in political science for some time, and it’s difficult to find electoral analysis that doesn’t in some way harp on the growing chasm between left and right. What ought not to be lost, however, is the fact that resentment of corporate power, economic inequality, and the influence of “elites” resonates on both ends of the political spectrum. Suspicion of corporations and concentrated wealth certainly isn’t new to leftist politics, but Bernie Sander’s campaign critiques of “the millionaires and billionaires” broadened the appeal and galvanized support more sharply than the left has done in decades.

On the right, Trump embraced protectionist rhetoric and won over blue-collar union households across the Rust Belt in part by promising to empower the working class who felt left behind during the recovery from the 2008 recession. Other Republican primary candidates attacked big business for its reliance upon big government and its support of liberal causes (immigration, gay rights, etc.). Anti-corporate sentiment, thus, crosses the political spectrum and, in so doing, is less tethered to political identification than it has been in recent memory.

Administration Policy is Likely to Inflame Anger on Both Sides

Contrary to Trump’s campaign rhetoric, his administration is poised to be the most pro-corporate since the Great Depression. His cabinet has deep and extensive ties to big business, and includes three billionaires and five former CEOs. More recently, the Wall Street aligned “Kushner camp” has reportedly become the dominant influence within the White House. Trump has issued an Executive Order requiring two regulations to be rescinded for every new one promulgated, and just this week has proposed cutting corporate taxes by more than half, from 35% to 15%.

A pro-business federal government and an increasingly anti-corporate electorate is a recipe for conflict and hostility. Anger towards corporations is likely to spread and to grow more intense. The average juror is likely to become more likely to harbor anti-corporate sentiments, and to feel angry that big business is benefitting at his or her expense.

The Jury Box Instead of the Ballot Box?

Tens of millions of Americans are already dissatisfied with the status quo and with the administration. Trump entered office with historically low approval ratings and reached majority-disapproval faster than any president measured with modern polling (since 1945). Americans who opposed Trump may feel hopeless and angry, and his pro-business policies run a serious risk of alienating and angering his blue collar supporters. If the Women’s March, the Science March and pro-immigration rallies at airports are any sign, the coming months and years are likely to bring very, very high levels of social unrest and activism.

What does this mean for corporate defendants facing an increasingly hostile and active populace in many venues across the country? It is clearly a dangerous environment for corporate defendants. Increased activism and anti-corporate anger may mean more and more jurors who see serving on a civil jury as a chance to right the “wrongs” of a political system they see as increasingly tilted to favor big business. Verdicts may become opportunities to fix what their votes could not.

We may see a rise in jury nullification with jurors increasingly willing to ignore the law or follow what they consider the spirit rather than the letter of the law. Jurors may be increasingly primed to accept plaintiffs’ arguments that verdicts should “send a message” and “change the way these companies do business” through punitive or large compensatory awards. And you can be assured plaintiff counsel are aware of and planning to seize on such sentiment, as it dovetails perfectly with en vogue “reptile” arguments about the importance of protecting the community.

Such jurors have of course always existed, but we anticipate their number will rise substantially in the near future. Further, as this mindset becomes more commonplace, there is a strong likelihood that it will become the norm rather than the exception in certain venues.

So What is a Corporate Defendant to Do?

Jury selection will be even more important for corporate defendants as they try to uncover and eliminate (via cause or peremptory strikes) such angry and activist jurors. Using juror questionnaires and/or voir dire to uncover anti-corporate sentiment and biases against big business will increasingly be a crucial part of the process. Precisely designed questions and probing follow-up must be deployed whenever possible; defense counsel will need to take care to ensure such questions pass muster with judges who may be reticent to allow jurors’ political and/or social views to be probed.

There is, of course, a greater chance of stealth jurors who lie to get on a jury to exact revenge and make a statement. To identify such jurors, questions that measure the internal consistency and reliability of a juror’s answers need to be designed and tested.

Social media research will likely increase in value as expressions of anti-corporate sentiment become more prevalent and acceptable. In fact, such research may become essential (if it isn’t already) as a tool for jury selection and monitoring seated juries. But, what happens when jurors begin to resist such probes into their private lives? Can a juror demand assurance from the court that their social media not be scrutinized? What happens when they demand that the parties not be allowed to research them just as they are instructed not to research the parties? In an increasingly polarized environment, these issues may reach a boiling point and, perhaps even, threaten the fabric of the jury system.

Case presentations will increasingly need to anticipate and head-off plaintiff’s attempts to tap into anti-corporate sentiment. Telling an effective “company story” is an important piece of this. Educating jurors about the defendant’s commitment to safety and/or the community, making clear how company policies are ethical and appropriately enforced, and highlighting any relevant commendations the company has received are all important elements of this.

If a company witness is called, they must be prepared to serve as the face of the company and speak authoritatively on the company’s relevant conduct. But, as we saw with the recent United Airlines controversy, in this day and age an executive – whether speaking to the public or testifying to a jury – cannot just parrot the corporate policy or position. They need to speak from their heart as well as their head to ensure they retain credibility.

In the current climate, defendants should also consider using corporate witnesses who are working in the trenches rather than the executive suite. While such “boots on the ground” employees may lack the educational pedigree or polish of upper management, they often possess common sense credibility and have intimate knowledge of the involved systems that can directly refute plaintiff’s theory without triggering images of corporate greed or excess.

In short, corporate defendants need to re-think conventional trial strategies in order to minimize the risk a jury will see their verdict as an opportunity to send a message to big business.

Written by Stephen Duffy and Alex Jakle.