Only July 8, the Eighth Judicial District in Nevada issued an order allowing a high-profile…

Making Your Damages Argument Persuasive

Although the American public is more sophisticated today about jury trials than it was ten or even five years ago, damage awards continue to be an issue about which the public is unsure. The amount of damages to award in many cases fits all of the characteristics of an ambiguous situation for jurors. They do not know how much money is right and they have little in the way of experience or external reality checks to judge the value of a claim.

One example of the dilemma of an ambiguous situation occurs when people drive through a heavy fog. Drivers in this situation usually drive faster than they think they are driving because they do not have any external references on which to base their true speed. In many foggy locations in England where this phenomenon was discovered, yellow strips were painted on the road closer together than normal to provide an external referent to slow drivers down. In a sense, drivers were tricked into slowing down because the road strips were placed closer together than they usually were.

Social psychology researchers have examined the impact of an ambiguous context in a phenomenon called the “autokinetic effect.” It occurs when an individual looks at a tiny point of light in a totally darkened room. At the beginning of the experiment, subjects are told that they will be asked to evaluate how much the dot of light moves, and are told to concentrate on the dot. Although the dot does not move, as the person stares at the dot of light, it appears to move, often erratically. In this ambiguous situation, where there is no external referent, people are easily influenced by the information they receive at the beginning of the experiment suggesting that the dot will move.

Knowing that jurors are in an ambiguous situation and are subject to being influenced, it is important that attorneys arguing damages take advantage of strategies for influence. The simple fact that the jurors have been called to the courtroom means that there is an expectation that someone has been damaged and some money is to be awarded. Effective damages themes must overcome this expectation from the outset of voir dire, and be reiterated throughout the trial. In deliberations, the jurors should no longer find themselves in an ambiguous situation as they are confronted with the decisions they will need to make on damages.

Two Views on Damages

Discussions with plaintiff and defense attorneys about damages being awarded by juries reveals an uncommon agreement. Both sides feel there is a problem, some say a crisis. However, whereas plaintiff attorneys feel the crisis is the difficulty in winning monetary damages from juries, defense attorneys feel that juries today are awarding astronomical sums of money to plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs feel jurors are unwilling to award damages for personal injuries. They point to the fact that in soft tissue motor vehicle cases it is getting more difficult to get the same amount in damages. Defense attorneys focus more on the large awards and the risks defendants run in the face of a possible runaway jury.

Whichever side is correct on the issue of whether too few or too many awards are being made by American juries, both sides point to the concern all attorneys have with the uncertainties and risks they face with regard to the amount of damages jurors will award.

Two Dilemmas: Sympathy and Anger

Sympathy

In order to prevail on damages and liability there are two common juror reactions to a case that need to be examined: sympathy for the plaintiff and anger toward the defendant. In cases with loss of a family member, crippling injuries, or financial ruin it is natural for jurors to feel sympathy for the injured party. It is the defendant’s challenge to acknowledge and remove sympathy associated with a tragedy.

Most often elimination of sympathy begins in voir dire and is repeated in opening statement and closing argument. Post-trial interviews with jurors in successfully defended cases often illustrate the fact that jurors wrestled with the issue of sympathy but were able to set it aside. In a case involving major personal injury:

- “We all felt sympathy for the plaintiff, she lost her husband. Sympathy came up in deliberations, but we discussed how that was not the issue.”

- “The defense attorney mentioned about ruling out sympathy, and the judge kept reminding us of our duty.”

Anger

There is no doubt that anger toward the defendant fuels damage awards. Whereas for sympathy, it is socially acceptable for a defense attorney to argue that everyone will feel sad and have sympathy for the plaintiff, there is not an easy way to block feelings of anger that might emerge in a trial. We are all familiar with the inflammatory arguments that plaintiff attorneys can make in response to allegations of corporate misconduct. In terms of mitigating jurors’ anger towards a company, it is important that the jury not only see the bad acts of the company, but also learn about the ways in which the company has taken responsibility for its actions regarding issues such as employee safety, product safety, fair employment practices, and compliance with regulatory agencies.

Anger flows from beliefs about responsibility and blame for a problem. According to the “just world theory,” (Lerner, M.J. & Meindl, J. R. “Justice and Altruism.” In J.P. Rushton and R. M. Sorrento (eds.) Altruism and Helping Behavior, Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum: 213-32 (1981)) people have difficulty accepting the injustices of life and have a strong need to believe that the world is just. If the world is just, it means that our own outcomes are controllable. In other words, people who do good deeds can expect rewards or profits. Jurors, therefore, will have a tendency to want to even out inequities and seek justice. They wish to assign responsibility for injustice and bring about restitution to injured parties. It is therefore incumbent on the defense to persuade the jury that justice sometimes means that the plaintiff (typically considered the underdog) goes home without money.

Case Themes

What are case themes and why are they important?

Research in a variety of applied fields has demonstrated the significance of themes for organizing information and making decisions. Every experienced trial attorney understands that jurors need to be able to have some way of organizing all the information they are exposed to during a trial. To persuade a jury, an attorney needs to develop case themes that help organize the diverse case facts and convey the case theory. Case themes can provide a bridge and a way for jurors to understand what they are learning during a trial. For many cases, themes are as important for damages decisions as they are for liability. To affect damages awards, attorneys need to influence jurors on the issues of responsibility, blame, and justice.

Obstacles to Juror Acceptance of Themes

Juror Confusion and Anxiety

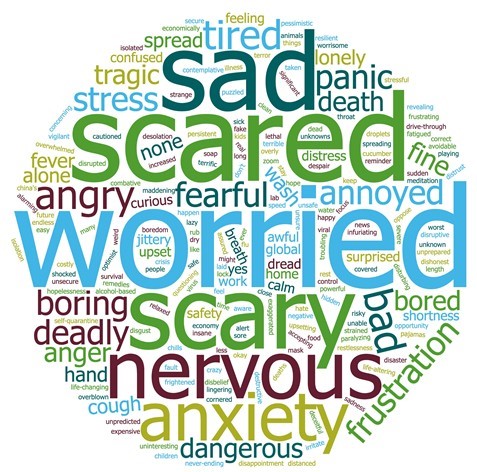

At the beginning of a trial, jurors are often anxious about having to serve on a jury because of the effect jury service will have on their personal life, and concern about the job they will have to do. This confusion about their role is enhanced if they feel they do not understand what the case is about. Confused and overly anxious jurors are often lost during a trial and often become so frustrated that they give up trying to understand the case (Graeven, D. “Juror Anxiety.” The National Law Journal, September 26, 1994: A21). Since this confusion can interfere with acceptance of case themes, it is important that jurors understand what their role will be. Attorneys need to do what they can to facilitate juror understanding of their role and the decisions they have to make. At a minimum, case issues should be pointed out during voir dire, and the verdict form should be discussed during closing arguments.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is one of the psychological concepts that affects jurors’ decision making when attributing cause and responsibility to an individual for an event. Hindsight bias is an individual’s tendency to see events as expected after they have occurred, even when they were seen as unlikely prior to their happening. This tends to increase feelings of confidence in judgement after the fact, and can lead to continued use of faulty decision strategies. (Heath, L. & Tindale, S. “Heuristics and Biases in Applied Settings.” In: L. Heath, R. S. Tindale, J. Edwards, E. Posavac, F. Bryant, E. Henderson-King, Y. Suarez-Balcazar, J. Myers (Eds.), Applications of Heuristics and Biases to Social Issues, New York: Plenum Press: 8-10 (1994)).

Most defense attorneys are well aware of ‘Monday Morning Quarterbacking’ and the way it can be used to second guess a decision by a defendant. A number of studies have been done which show that hindsight bias is very difficult to overcome, even among sophisticated decision makers. If hindsight bias is present in a case, one of the few things that can be done is to educate jurors about hindsight bias: “If something bad happens, we have a tendency to think that we should have known it would have happened.” The hope would be that at least one juror understands that idea and could use it in deliberations.

Failure to Understand the Law

Jurors often spend a considerable amount of time in deliberations trying to understand the laws that apply to a case. Research on jury deliberations has shown that the most common source of jury error is not difficulty understanding the facts, but trouble understanding the legal instructions (Ellsworth, P. “Are Twelve Heads Better Than One? Law and Contemporary Problems, 55: 204-224 (1989)). Since defendants often benefit from jurors use of the law, there are several things defense counsel needs to do to improve juror understanding of the law.

It is important that the verdict form be clearly explained to the jury in closing arguments. It is not uncommon in complex cases for jurors to be confused about which way they should vote on a certain issue if they favor a certain side. That confusion needs to be eliminated.

Another approach to improving juror understanding of the law is for defense counsel to ask the court to pre-instruct the jury on the law prior to hearing any evidence. Pre-instruction of the jury maximizes the effect of the law on the reaction of the jurors to the case arguments.

Conclusion

Jurors come to the issue of damages often lacking guidelines as to what is appropriate. In an ambiguous situation, such as the one jurors confront on the issue of damages, attorneys have an opportunity to persuade jurors by using case themes. Case themes are the frontline of defense and can be an effective tool that can be used to help frame jurors’ reactions to issues of responsibility and blame.