The question we’ve been asked the most by clients the past few months is:…

Juror Attitudes in Trucking Litigation

Assessing Juror Attitudes in Trucking Litigation

In approaching jury selection in trucking litigation, it is important to be aware of the unique challenges that this type of litigation presents, as well as those issues defendants normally have to face in other types of litigation. As a window into these issues, the Federal Highway Office of Motor Carriers conducted a series of focus groups of car and truck drivers around the country to assess attitudes toward trucks and truck drivers. The findings from that focus group series was that most drivers:

- believe that passenger car driver error is the main cause of car/truck collisions.

- like truck drivers, but dislike trucks.

- feel intimidated by the size, weight and speed of trucks.

- believe that commercial driver license training should be upgraded (longer training, periodic retesting).

- see a need for public education programs on safety when sharing the road with trucks.

- believe that large trucking companies have better equipment and better trained drivers than smaller companies.

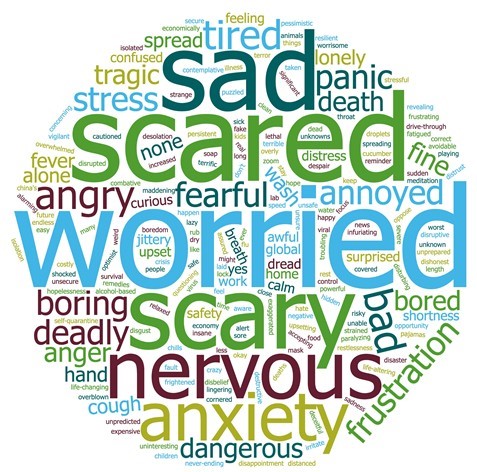

Jurors can have strong emotions about truck related litigation. Trucks can scare people. Motor vehicle litigation, with skillful verbal and visual reenactments of accidents, can push these emotional buttons. No matter what jurors’ general beliefs about trucking companies or drivers, all jurors can have strong emotional reactions (anger and fear) to certain scenarios. For example, a truck coming up fast from the rear on a car produces a strong visceral reaction in driver and passenger. A truck passing a slow-moving car in a rain storm also activates fear in most occupants of a car. These events also can trigger comments and less than flattering gestures from drivers. The following are some comments from respondents to a survey on whether speed limits for trucks should be raised.

“Trucks are the real terrorism in America.”

“Trucks are less likely to sustain damage in an accident with a small car. As a result, truck drivers are often the most fearless and dangerous drivers.”

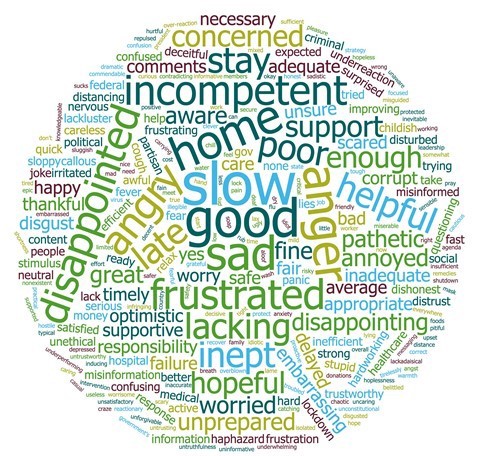

Selecting a jury in a catastrophic truck crash case requires an awareness of the fact that despite what people say they believe about trucks, there is a potential reservoir of fear and anger that an aggressive plaintiff presentation can activate. In addition to jurors’ personal experiences, media reports about truck accidents create a challenge for the attorney defending one of these major accident cases. This challenge of identifying those jurors whose anger will impact their processing of information is one of the unique challenges in trucking major accident litigation.

Juror Anxiety About Trucks, Accidents And Driving

Juror anxiety about driving, accidents and trucks may sound like an unusual area of inquiry for jury selection. However, these areas are topics that some jurors are very anxious about and, unless asked, they tend not to mention their feelings in voir dire. Anxiety affects jurors’ ability to think logically as well as their inclination to make sense of the evidence presented. Attorneys who try major truck cases need to identify those individuals who worry or who are overly worried about accidents, driving and have a fear of trucks.

Just as someone who has test anxiety will fail to perform well on an exam, a juror with high anxiety is less likely to comprehend information presented at trial. The anxious juror is unpredictable and more likely to be a “loose cannon.” Since decision making by an anxious juror tends to be illogical, they can harm either side in a lawsuit. Generally though, defense attorneys are more concerned about removing the anxious juror.

There are several approaches to identifying anxious jurors. One method is to look at the behavior or lifestyle of an individual to determine if they act in a way that demonstrates anxiety. These behaviors would include individuals who have a driver’s license, but choose not to drive or choose to place strong limits on their driving. Another red flag behavior would be people who do not like to drive on a freeway at night, or who see the freeway as a very dangerous place. People who behave in an overly cautious way usually exhibit high levels of anxiety.

Another approach in identifying the overly anxious individual is to discover whether a potential juror refuses to accept a fact that should have the effect of reducing their anxiety. Jurors with high levels of anxiety are not as open to the idea that circumstances which trouble them can or will improve. Instead, they focus on information that supports rather than alleviates their anxiety. For example, even if the number of major trucking accidents is known to be declining, an individual who has hesitation believing that fact would probably not be open to the defense’s arguments.

The Role of Cause, Responsibility and Blame in Juror Decision Making

There are a number of ways of looking at a truck accident that facilitate an attorney’s ability to address the issues of cause, responsibility and blame for the event. The sources for these ideas are derived from state-of-the-art theory and research on juror decision making. Two of the concepts involved in jurors’ evaluation of cause, responsibility and blame are explored below.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is one of the psychological concepts that affects jurors’ decision making when attributing cause and responsibility to an individual for an event. Linda Heath and Scott Tindale describe hindsight bias as an individual’s “tendency to see events as expected after they have occurred, even when they were seen as unlikely prior to their happening. This tends to increase feelings of confidence in judgement after the fact, and can lead to continued use of faulty decision strategies.” (Heath and Tindale, 1994.) For example, if a truck driver was driving down a steep grade behind a passenger car at a safe distance in the rain and he lost his brakes, resulting in a collision between the truck and passenger car. A juror using hindsight bias may say, “The truck driver should have known to leave more space between himself and the car in case he had a problem with his truck, especially since it was raining.” In this case, the truck driver could not have foreseen the brake failure, but the juror, having the benefit of knowing the outcome, attributes the cause of the accident to the truck driver’s “negligence.” Based on the juror’s conception of cause, they can now assign more responsibility for the accident on the truck driver than on other individuals or factors, and thus easily blame the truck driver’s actions, or lack there of, for the catastrophe.

Counterfactual Thinking

Another concept that jurors use when evaluating an event is counterfactual thinking. Counterfactual thinking occurs when a person evaluates an event by how easily it could have been undone to create a different outcome, usually a more positive outcome. For instance, using the example illustrated above, a juror might consider the cause of the accident and say, “If only the truck driver had checked his brakes at the rest stop, he would not have had this accident,” or “If only the truck driver had left more space in front of him, he could have swerved to the side and avoided hitting the car in front of him.”

The ease with which a juror can undue the negative event with a counterfactual like the ones illustrated above, affect the amount of blame they attribute to the truck driver. If it is hard for jurors to develop reasonable counterfactuals, it will be harder for them to attribute responsibility, and thus blame, to the truck driver. On the other hand, the more counterfactuals a juror can create to prevent the accident, the stronger their opinions of blame on the party who they feel could have changed the outcome of the event, in this case the truck driver. By creating counterfactuals, jurors are constructing alternative realities. Subsequently, when jurors make judgements about the event, they are making judgements based on an alternative reality.

Addressing Issues of Responsibility and Blame

Carefully developed case themes and theories can help a defense attorney overcome these elements of juror decision making. To do this, the attorney must consider all the different ways a juror might analyze an accident and develop a plan of attack to break those theories and perceptions down before jurors have an opportunity to build them up. For instance, one strategy to combat counterfactual thinking is to block the process jurors use to develop their counterfactuals. For example, the defense attorney in the example used above might say, “Even if it had not been raining and the truck driver had been another 100 ft. back, he still would have hit the car in front of him from the unexpected loss of his brakes.” The point of this strategy is to show the jurors that “even if” you change some of the circumstances surrounding the event, you may still have the same outcome. This strategy moves the responsibility from the truck driver to external factors beyond his control. One of the ways to deal with hindsight bias is to introduce it as a concept in voir dire. In voir dire, jurors can be asked if they have ever heard of hindsight bias or “Monday-morning quarterbacking.” Then in opening statements, hindsight bias can be brought up again to educate the jurors on the concept.

Key Juror Attitudes To Determine In Voir Dire

Truck Safety

- Extent to which regulations regarding trucks are being enforced.

- Extent to which regulations are being broken by drivers and truck companies.

- Whether trucks are more or less safe today than they were 10 years ago. What about 20 years ago?

Truck Accidents

- Experience with accidents involving a truck: Have you, or anyone close to you, ever been in an accident involving a truck?

- Experience with debris from a truck: Have you ever been in a vehicle that was damaged by debris from a truck?

- Whether accident rates involving trucks are increasing or decreasing.

- Opinions on the main causes of truck accidents.

Truck Companies

- Extent to which drivers put money ahead of safety.

- Extent to which companies put profits ahead of safety.

- Whether truck companies push their drivers to work too hard (too long).

- Extent of truck company concern about their drivers.

Truck Drivers

- Extent of concern for the public and their safety.

- Extent to which truck drivers have to work fast to make money.

- Whether drivers receive enough training these days. More or less than in the past?

- Whether truck drivers push themselves to work too hard (too long).

- Beliefs About Multi-Trailer Larger Combination Vehicles (LCVs).

- Type of Responsibilities Car Drivers Have in Driving Around Large Trucks: Is the burden on the trucker or the car driver?

Developing Cause Challenges

Judges typically do not like to grant cause challenges. However, an experienced trial attorney knows how to achieve cause challenges and is willing to go the extra distance to obtain such a challenge. The motivation and ability of attorneys to achieve cause challenges vary widely, but these are skills that can be learned.

In achieving cause challenges, there are several steps involved.

Adopt a proper attitude and demeanor

Jurors who admit to bias usually will only do it if they are speaking with someone who appears to understand them. Bias is almost never admitted under conditions approximating cross examination. One key is to talk slowly with the juror and to use pauses to create social pressure. This empathic demeanor is highly effective at getting jurors to confirm their prejudices.

As a corollary to observations about demeanor, it is also true that it is easier to get challenges granted for feelings of sympathy or compassion rather than for feelings of anger or hostility. Judges appear more understanding and less aggressive about rehabilitating a juror who feels sorry for a victim than for a juror who simply dislikes truck drivers or trucking companies. In cases where sympathy will be an issue, this is often the more fertile area of voir dire for cause challenges.

Establish the grounds for cause

This may be done by referring either to the questionnaire responses or prospective jurors’ responses in oral voir dire. For example:

“You said you didn’t trust truck drivers. You also said truck drivers do not care about automobile drivers.”

Don’t hit prospective jurors over their heads with the notion of being fair

Typically, the ones you want off do not like to admit that they can’t be fair. Besides, prospective jurors are often offended by the suggestion that they might be anything but fair.

Use metaphors

Since prospective jurors will seldom say that they can not be fair, the most effective approach an attorney can use is to provide a socially acceptable way to talk about bias. Generally, after the grounds for bias have been established, the strategy is to use some type of metaphor to probe further. Examples include:

“Given what you said before (or, based on your questionnaire), would the defendant start with a bit of an edge?”

“Would the plaintiff have a little steeper hill to climb to prove its case?”

“Would the defendant be starting a little bit behind the plaintiff?”

“If this trial was a race, would we be starting one step behind?”

“If you were in my shoes, representing my client, would you want a person with your views sitting as a juror?”

“Do you tend to side with the underdog? Do you see the plaintiff as the underdog in this case?”

After they have agreed with the metaphor, the attorneys then have to raise the level of commitment and suggest that they might have a more difficult time being fair.

Know when to stop

A problem may arise if the defense continues questioning after cause has been established: rehabilitating the person. This problem is most likely to occur when co-counsel does follow-up questioning. Occasionally, after an attorney goes back over the same territory, the juror says the “wrong thing.” A brief discussion on this point among all co-counsel before oral voir dire (or a note to stop questioning a particular juror) will usually suffice to minimize the problem.

Guidelines For Handling Jury Selection

Extensive research and observations of hundreds of jury selections suggest the following guidelines:

- Juror questionnaires should be used whenever possible. Juror questionnaires are discussed in greater detail later in this paper. They represent one way for a trial attorney to cut through barriers created by the courtroom setting and allow for the determination of juror attitudes on critical issues.

- Cause challenges must be aggressively pursued.

- In camera or chambers voir dire is extremely helpful for cases involving highly sensitive or personal issues. Jurors are more candid in a more private setting. This procedure can and is often handled while the other jurors have been dismissed for a break.

- Tackle the tough issues in voir dire and in juror questionnaires. Attorneys often avoid asking the most critical jury selection questions because of concerns about appearing insensitive to jurors. Our view is to ask the tough questions and get the best jury.

- Keep a good pace and avoid organizational housekeeping delays. Jurors do not appreciate delays.

- Greater attention needs to be paid to the selection of alternate jurors. In a typical major catastrophe case lasting several weeks, an alternate juror will likely be required to serve as a deliberating juror. Our research has shown that alternate jurors tend to be more biased than regularly seated jurors. This is in large part because not as much attention or time is given to scrutinizing alternate jurors.

Practical Strategies For Using A Juror Questionnaire

Jury experts agree that potential juror questionnaires to supplement voir dire can greatly improve the jury selection process. It does not appear that these questionnaires have been used as much as they should be in trucking accident litigation. The information learned through the questionnaire improves the voir dire process by allowing the attorney to focus on both individuals and specific topics. Benefits of juror questionnaires include:

More Candid Responses By Jurors

The courtroom setting is not conducive to open discussion.

Minimizing The Risk That One Juror’s Extreme Opinions Will Contaminate The Rest Of The Panel

If one or more of the potential jurors have had an extremely negative experience with truckers or a truck related accident, this can cast a negative pall upon the remaining process. Juror questionnaires remove this bias, and help to identify people who may be better questioned at the bench during voir dire.

Reducing The Time Needed For Voir Dire

A problem with voir dire is that to really probe the jurors, each person needs to be asked similar questions. Jurors often feel resentful and tire quickly of the repetition. They become more reluctant to speak, and are more likely to give common answers because it is easier. This voir dire is often of limited value as an assessment tool of juror bias. Juror questionnaires help to structure the voir dire process and avoid this problem.

Research has found that many judges are likely at least to consider a juror questionnaire. In a survey of Northern California federal and superior court judges, more than 90% of the judges were willing to consider use of a juror questionnaire, and two thirds have actually used them. Research from Los Angeles has shown that while 66% of Superior Court judges have used questionnaires, almost all would consider their use. In a similar survey of Texas federal and superior court judges, more than half of the judges would consider using questionnaires. Judges are especially likely to consider use of juror questionnaires in long cases, in complex or multiple part cases, and in cases involving sensitive issues.

When judges resist administering a questionnaire, it is usually because they consider it a waste of time. These objections can be overcome by designing a much shorter questionnaire. Demographic questions asked by the court, such as age, residence, and work history, are redundant when included in a questionnaire and thus can be left out.